Emily McCormick is Vice President of Editorial & Research for Bank Director. Emily oversees research projects, from in-depth reports to Bank Director’s annual surveys on M&A, risk, compensation, governance and technology. She also manages content for the Bank Services Program, including Bank Director’s Online Training Series. In addition to speaking and moderating discussions at Bank Director’s in-person and virtual events, Emily writes and edits for Bank Director magazine, BankDirector.com and Bank Director’s weekly newsletter, The Slant. She started her career in the circulation department at the Knoxville News-Sentinel and graduated summa cum laude from The University of Tennessee with a bachelor’s degree in Spanish and International Business.

How Two Sellers Crafted the Best Deal for Their Bank

Evaluating prospective partners can help bank leaders understand their strategic options — and earn a better price if they sell.

On May 1, Kalispell, Montana-based Glacier Bancorp closed its acquisition of $1.3 billion Bank of Idaho Holding Co., a deal that was announced on Jan. 13. Recent deals like this one could signal better pricing for sellers in 2025. But it’s not just price that gets sellers to sign the dotted line.

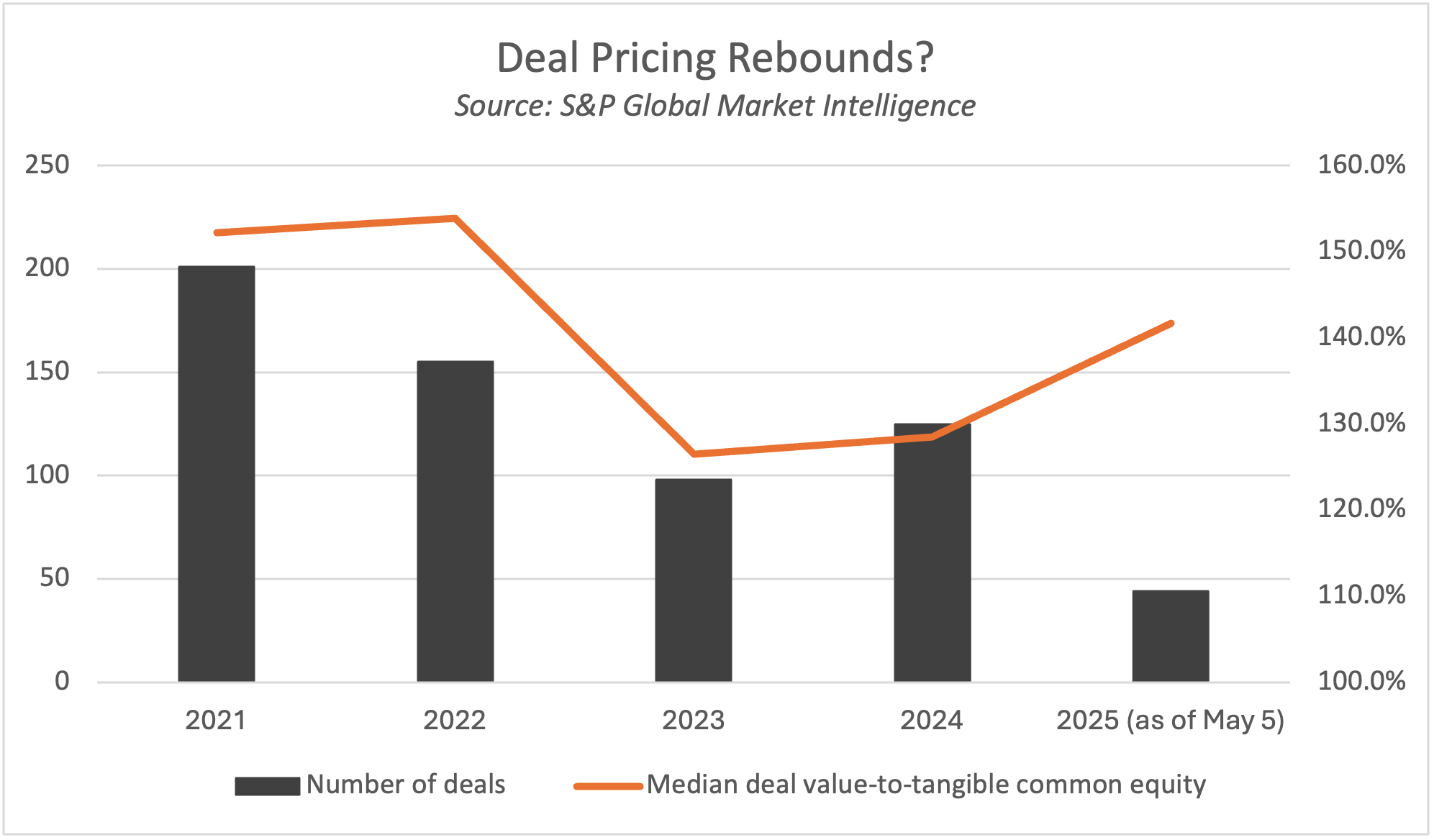

Bank of Idaho was priced at a deal value-to-tangible common equity ratio of 186.7% at announcement, according to S&P Global Market Intelligence — the highest price of all transactions announced in 2025 through April 30. That compares to a median 141.7% for the 44 transactions announced year-to-date through May 5, according to S&P. But compared to the previous two years, deal pricing is trending up. In 2024, 125 deals were announced at a median 128.5% deal value-to-tangible common equity. In 2023, there were just 98 transactions at a paltry median of 126.5%.

Glacier wasn’t the only bidder for Bank of Idaho; a credit union made an offer. But Bank of Idaho evaluated the price offered by Glacier — 100% stock at $52.47 per share, according to Glacier’s investor presentation — and its performance as a publicly traded bank. That, coupled with Glacier’s culture and its experience as an acquirer, made it the better transaction, explains Jeff Newgard, who was Bank of Idaho’s CEO and chairman. And there’s more to a good deal than price. Newgard felt confident in the decision because he spent time getting to know prospective buyers and sellers over the years, including Glacier CEO Randall Chesler.

Christopher Olsen, managing partner at the investment bank Olsen Palmer, says this can be time well spent. There are two to five years of prep work prospective sellers could be doing that could include getting to know potential partners, understanding the bank’s value and its priorities, and taking steps to achieve the best shareholder outcome, he says. That extra work can improve pricing and provide clarity on other aspects of the deal, such as cultural fit. Sellers can also assess the buyer’s ability to execute and the future valuation of its stock.

“If done successfully, the pre-existing relationship gives a buyer appreciable insight into the seller’s culture, business model, talent pool, underwriting and credit process, future prospects, and other areas,” Olsen says. That certainty can yield a stronger valuation.

Newgard wasn’t planning to sell Bank of Idaho. But he’s always been open to selling.

“I love making my investors a lot of money,” says Newgard. That meant keeping Bank of Idaho’s strategic options open. “How do we create the most value for our shareholders?” he says. “That might be buying a bank. It might be entering new markets. It might be adding teams that create a bigger economic engine. And it might be, if you team up with the right partner, to sell.”

The Choice to Sell

During its annual strategic planning process in September 2023, the board at Defiance, Ohio-based Premier Financial Corp. decided to explore a sale, says former Premier executive chairman Donald Hileman. The $10 billion asset threshold loomed for the $8.6 billion bank, a barrier that can result in lost debit card fee income, increased costs and heightened regulatory expectations. The board also wanted a better currency for shareholders. “We were growing our franchise,” he says, “but our valuation was a little more stagnant than we would have liked.”

Hileman started talking to prospective buyers, a list of around 10 banks that bank leaders ultimately whittled down to two. Some of those entities weren’t ready for a deal, he says, due to a recent acquisition or technology integration. Others couldn’t pay the multiple Premier’s board believed the bank deserved.

The board created a list of priorities early in the process that included community involvement, cultural alignment and a strong currency. Board representation was also important. Wesbanco, in Wheeling, West Virginia, best fit the bill. “Wesbanco’s currency fit a lot of the criteria we wanted,” says Hileman. “More liquidity, growth market, good multiples.” The deal closed on Feb. 28. The acquisition valued Premier at 141.9% deal value-to-tangible common equity when it was announced, per S&P. Wesbanco now has $27 billion in assets.

Olsen advises prospective sellers to come up with a list of what they want from a buyer. Price tends to rate highly, he says, but the criteria may also include culture, and how the deal would affect employees and customers.

Newgard wanted a partner with the currency and interest to do a deal, along with an ability to execute. “Execution is everything,” he says. “Can they get the deal done? Do they have the respect and support of the regulators? Do they have a [liquid] currency? Have they done it before?” Glacier’s acquisition of Bank of Idaho is its 12th announced transaction in 10 years, according to the company.

Getting Real About Price

Price can be the greatest sticking point in a deal, however. In Bank Director’s 2025 Bank M&A Survey, 46% said their board and management team would be open to selling their bank over the next five years — at the right price. For 36%, that would be at least 1.5 times book value; 55% would want more.

An understanding of current market conditions will help the board have a clear view on pricing, says Olsen. He regularly briefs boards on their bank’s valuation and explains what’s driving that number, including the impacts of unrealized losses in the bond portfolio.

“At the end of the day, sellers have explicit fiduciary duties,” says Olsen. That includes price, but there are other considerations. If there’s stock in the transaction, is that a good long-term investment? Can the buyer get the cash needed for the deal? Can they get regulatory approval so the deal crosses the finish line?

He also advises potential sellers to review their contractual obligations, including vendor contracts and employment agreements. Loan files could be fully imaged to ease due diligence.

A “Win” for Shareholders

Banks tend to have an independent mindset and don’t plan to sell — until things change, says Olsen. Shareholders may want cash for their shares, or there’s no successor for a retiring CEO. They’ll likely find a seller, he says, but “they missed the opportunity to network years in advance.”

The selling process can range from exclusive and closed — a one-on-one negotiation with a buyer — to a wide open, full auction. His firm sometimes starts with informal conversations with a limited number of potential buyers. The seller could then select a smaller group of ideal partners and formally solicit bids. That approach, he says, is “the most discreet. You get the best optionality, you get the best fit. It just takes a lot of time, and you need to plan in advance for that.”

Selling the bank can seem bittersweet, but Newgard sees Bank of Idaho’s acquisition as a win for shareholders, as well as customers and employees who can leverage a bigger balance sheet, a larger footprint and more technology. “I was able to make the shareholders a lot of money,” he says, “and take care of all my stakeholders.”