The Powerful Force Driving Bank Consolidation

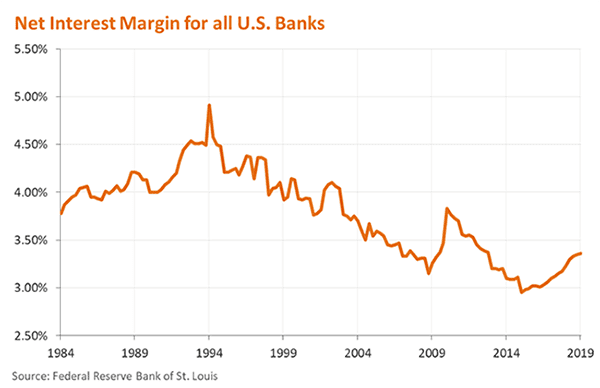

A decades-old trend that has helped drive consolidation in the banking industry can be summarized in a single chart.

A decades-old trend that has helped drive consolidation in the banking industry can be summarized in a single chart.

In 1995, the industry’s net interest margin, or NIM, was 4.25%, according to the Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis. (NIM reflects the difference between a bank’s cost of funds and what it earns on its assets, primarily loans.) Twenty years later, the margin dropped to a historic low of 2.98%, before gradually recovering to 3.30% last year.

The vast majority of banks in this county are spread lenders, making most of their money off the difference between what they pay for deposits and what they charge for loans. When this spread narrows, as it has since the mid-1990s, it pinches their profitability.

The decision by the Federal Reserve’s Federal Open Market Committee to reduce the target range for the federal funds rate by 25 basis points in August will likely exacerbate this by reducing the rates that banks can charge on loans.

“For most banks, net interest income [accounts for] the majority of their revenue,” says Allen Tischler, senior vice president at Moody’s Investor Service. “A reduction in [it] obviously undermines their ability to generate incremental earnings.”

There have been two recessions since the mid-1990s: a brief one in 2001 and the Great Recession in 2007 to 2009. The Federal Reserve cut interest rates in both instances. (Over time, lower rates depress margins, although banks may initially benefit if their deposit costs drop faster that their loan pricing.)

Inflation has also remained low since the mid-1990s — particularly since 2012, when it never rose above 2.4%. This is why the Fed has been able to keep rates so low.

Other factors contributing to the sustained decline in NIMs include intermittent periods of intense competition and rate cutting between banks, as well as the emergence of fintech lenders. Changes over time in a bank’s the mix of loans and securities, and among different loan categories, can impact NIMs, too.

The Dodd-Frank Act has exacerbated the downward trend in NIMs by requiring large banks to carry a higher share of low-yielding liquid assets on their balance sheets, which depresses their margins. This is why large banks have contributed disproportionally to the industry’s declining average margin – though, these institutions can more easily offset the compression because upwards of half their net revenue comes from fees.

Community banks haven’t experienced as much compression because they allocate a larger portion of their balance sheets to loans and do most of their lending in less-competitive markets. But smaller institutions are also less equipped to combat the compression, since fees make up only 11% of the net operating revenue at banks with less than $1 billion in assets, according to the Office of the Comptroller of the Currency.

The industry’s profitability has nevertheless held up, in part, because of improvements to operating efficiency, particularly at large banks. The corporate tax cut that went into effect in 2018 plays into this as well.

“If you recall how banking was done in 1995 versus today … there’s just [greater] efficiency across the board, when you think about what computer technology in particular has done in all service industries, not just banking,” says Norm Williams, deputy comptroller for economic and policy analysis at the OCC.

The Fed’s latest rate cut, combined with concerns about additional cuts if the escalating trade war with China weakens the U.S. economy, raises the specter that the industry’s margin could nosedive yet again.

Tischler at Moody’s believes that sustained margin pressure has been a factor in the industry’s consolidation since the mid-1990s. “That downward trend does undermine its profitability, and is part of the reason why the industry has consolidated as much as it has,” he says.

If the industry’s margin takes another plunge, it could drive further consolidation. “The industry has been consolidating for decades … and there’s no reason why that won’t continue,” says Tischler. “This just adds to the pressure.”

There were 11,971 U.S. banks and thrifts in 1995. Today there are 5,362. Given the direction of NIMs, it seems like we may still have too many.