Market Intelligence

As a general rule, even a moderately profitable bank will struggle to responsibly invest all its earnings into organic growth. There are only so many good loans to make in any market. Loading up on securities will impair a bank’s net interest margin. And mergers and acquisitions should be driven by the quality of available acquisition targets, not the amount of capital held by an acquirer. To earn a satisfactory return on equity, then, a bank must find other ways to deploy excess capital.

As a general rule, even a moderately profitable bank will struggle to responsibly invest all its earnings into organic growth. There are only so many good loans to make in any market. Loading up on securities will impair a bank’s net interest margin. And mergers and acquisitions should be driven by the quality of available acquisition targets, not the amount of capital held by an acquirer. To earn a satisfactory return on equity, then, a bank must find other ways to deploy excess capital.

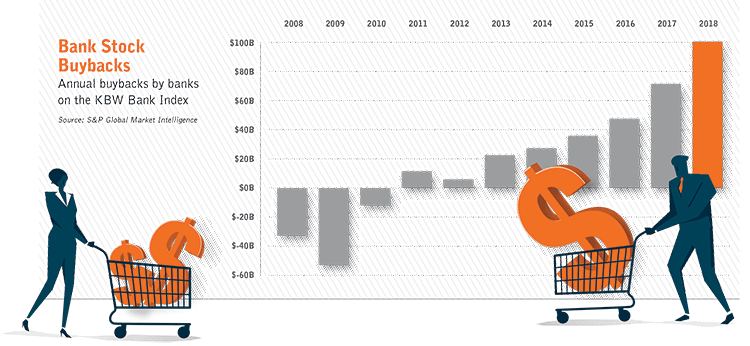

This is why banks are buying back so much stock right now. In 2018, the two dozen banks on the KBW Bank Index, which tracks the performance of large, publicly-traded banks based in the U.S., bought back a combined $100 billion worth of stock, according to data from S&P Global Market Intelligence. That was 42 percent higher than 2017, roughly double the amount repurchased by the same group in 2016 and about triple the amount of money spent by these banks on buybacks in 2015. Three banks alone-JPMorgan Chase & Co., Bank of America Corp. and Wells Fargo & Co.-repurchased more than $60 billion worth of stock last year, accounting for nearly two-thirds of all buybacks on the big bank index.

“Buybacks should not be done at the expense of investing appropriately in our company,” wrote JPMorgan Chairman and Chief Executive Office Jamie Dimon in his annual letter this year. “However, when you cannot see a clear use for your excess capital over the short term, buying back stock is an important capital tool-as long as you are buying it back at a reasonable price.”

Two factors explain the rapid growth in buybacks. The first is the tax cut that went into effect last year, dropping the corporate income tax rate from 35 percent down to 21 percent. This fueled record profits in the industry. U.S.-based banks earned a combined $237 billion last year, up from $164 billion in 2017, according to data from the Federal Deposit Insurance Corp. Additionally, for much of the past decade banks were focused on accumulating capital, not jettisoning it, in order to meet heightened capital requirements passed after the financial crisis. This was especially true for institutions subjected to the Comprehensive Capital Analysis and Review, the stress test administered each year by the Federal Reserve. But now that many banks are sitting on more capital than they know what to do with, the equation has changed.

Indeed, all but one company on the KBW Bank Index has consistently bought back stock over the past five years. That company is First Republic Bank, a $102 billion asset bank that serves high net worth clients in a handful of cities across the country. Over the past five years, its Tier 1 capital has grown at an annual rate of 16.3 percent. First Republic has used this to capitalize its unusually rapid organic growth, with loans and deposits at the San Francisco-based bank increasing at compound annual rates of 17 percent and 20 percent, respectively, since 2013. But this makes First Republic an exception to the rule, not the rule itself.

The Big Change in Banking

The banking industry has been through countless periods of technological upheaval, but none have altered the fundamental competitive dynamics of banking. The postal service enabled deposits by mail. The phone allowed customers to conveniently check account balances by talking to someone directly. The ATM empowered customers to transact without walking into a branch or talking to a person. And the internet took all these changes one step further, allowing customers to bank without leaving the comfort of their home or even calling someone on the phone.

The changes underway now in the banking industry nevertheless seem different. The introduction of the iPhone more than a decade ago, combined with younger generations of consumers who grew up using digital applications to get directions, order food and trade stocks, has led banks to rethink their business models. Banks are shuttering branches and investing heavily in technology. The chief executive officer of Bank of America Corp., Brian Moynihan, said recently that the $2.4 trillion bank spends approximately $10 billion a year on technology, of which $3 billion consists of “change the bank” initiatives.

Some have even posited that the source of competitive advantage in the banking industry has shifted over the past 10 years. In the 1950s and 1960s, a bank’s competitive advantage stemmed from the number and location of its branches. Then, when interest rates skyrocketed following the oil crises in the 1970s, banks began competing on rates and fees-that was the era of free checking accounts. Today, some believe that the ability to compete lies in the ability to quickly and nimbly integrate third-party applications. They compare the current banking industry to the computer industry two decades ago, when computer companies didn’t actually manufacture anything, but instead just packaged a series of hardware components made by others-hard drives, central processing units, video cards, etc.-into a unified product.

Are we to believe that the smartphone alone caused this upheaval? Is a device that fits into someone’s pocket really why the nation’s second biggest bank by assets has closed more than a quarter of its branches since 2009?

That’s what the prevailing narrative would lead one to believe, but there’s another factor at work as well. After a series of financial crisis-era acquisitions, there are three banks in the United States that each hold more than 10 percent of the nation’s total deposits-JPMorgan Chase & Co., Bank of America and Wells Fargo & Co. As a result, under the Riegle-Neal Act of 1994, which ushered in nationwide branch banking, these institutions can no longer make acquisitions. Their only avenue for expansion is organic growth. And the key to organic growth, as these banks see it, are digital distribution channels.

The shift in growth strategies at the nation’s biggest banks has far-reaching implications. Community and regional banks benefited for decades from big bank acquisitions. Smaller banks that wanted to sell could find buyers. Those that didn’t want to sell gained customers and deposits when local rivals were acquired by distant competitors-in some cases, 40 percent of deposits fled after a deal. And it’s the money that big banks once spent on acquisitions that is now funding investments in technology. The point being, while the smartphone may be the vehicle for the changes underway in banking today, it is not the sole impetus for those changes.

Join OUr Community

Bank Director’s annual Bank Services Membership Program combines Bank Director’s extensive online library of director training materials, conferences, our quarterly publication, and access to FinXTech Connect.

Become a Member

Our commitment to those leaders who believe a strong board makes a strong bank never wavers.