The Darwinian Banker @ PNC

- CEO Bill Demchak’s plans for a digital future.

- PNC invested $1 billion upgrading its core technology platform last year to transform its business.

- The bank’s profitability fell last year as it walked away from some price competition in the corporate lending market.

In his seminal work on evolution, Charles Darwin proposed that organisms that are highly adapted to their environment have the best chance of survival. Darwin’s theory of natural selection, described in “On the Origin of Species” and published in 1859, is particularly relevant for the banking industry today, which is facing the pressure to adapt to an increasingly disruptive environment. Darwin certainly wasn’t thinking about bankers when he introduced the world to evolutionary biology, but bankers should be thinking a lot about him and their own ability to evolve.

The disruptive forces confronting banks today are systemic and in some cases accelerating. The Great Recession might have ended in the summer of 2009, but the U.S. economy has failed to produce the level of robust growth that we’ve seen in past recoveries, which has kept interest rates low and squeezed the industry’s profit margins. The Dodd-Frank Act of 2010 imposed a new set of costly regulations on an industry that was already heavily regulated, while the Basel III reform measures significantly increased the industry’s capital requirements, contributing to lower shareholder returns. The Trump administration has promised to remedy some of these issues, through deregulation, a cut in the corporate tax rate or an infrastructure spending plan intended to stimulate the economy, but it’s unclear when any of these benefits will materialize, or what their actual impact would be.

The greatest disruptive threat facing bankers today is the epochal change occurring in retail distribution as consumers and businesses embrace digital commerce in ever increasing numbers, while aggressive financial technology companies muscle into the financial services market to meet that demand. Consumers and small businesses are a vital customer set for the industry, but they are increasingly choosing to do business through digital channels like mobile instead of branches, which impose a much higher cost on the banks. The growing preference for digital channels is forcing the entire industry to rethink its distribution strategy.

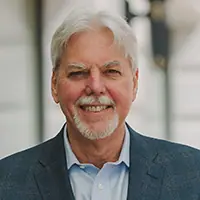

Some bankers are adapting to this Darwinian environment faster than others, and among the leaders is William S. “Bill” Demchak, chairman and chief executive officer at Pittsburgh-based PNC Financial Services Group. Demchak, 54, took over as CEO in April 2013 and assumed the chairman’s role a year later. He has a low-key manner, but has also earned a reputation for candor and is sometimes described as being “blunt.” He wins high marks for his analytical abilities, and Scott Siefers, a bank stock analyst who covers PNC for Sandler O’Neill + Partners, says that investors “look at him as being very cerebral, and thoughtful and objective.”

Demchak also has the paradoxical capacity to, simultaneously, be very conservative and very forward thinking in ways that benefit the company equally. In 2016, Demchak pulled PNC back from the corporate lending market because he didn’t like the pricing even though the bank ended up earning slightly less than it did in 2015. Investors wanted to see more loan growth, but he wasn’t afraid to be conservative because he believed there would be better opportunities this year. Demchak has also been investing heavily in technology, including PNC’s core systems and digital channels like mobile, while also repurposing its branches to focus more heavily on sales. Will these investments pay off? Demchak says the world is changing, and PNC has no choice but to change with it.

“People will say, ‘PNC is a low-risk bank and a conservative bank,’ Demchak said during an interview with Bank Director magazine. “Yet, very clearly, banking is going through not an evolutionary but a revolutionary change, perhaps bigger than when interstate banking opened up. As it relates to your product capacity you need to serve the client of tomorrow. We can’t afford to be ‘low risk.’ You’re high risk by the very nature that nobody knows what the future is.” The real risk, Demchak suggests, would be to do nothing. “I use the analogy all the time: You’re Blockbuster video trying to give away free popcorn, and Netflix is coming around the corner,” he says. “You’ve got to adapt.”

With $366 billion in assets, PNC is the seventh largest commercial bank holding company in the United States (or ninth largest if you include the investment banks Goldman Sachs and Morgan Stanley). The company traces its history to the Pittsburgh Trust and Savings Co., which was established in 1845. In 1863, it became the first bank in the country to apply for a national charter after passage of the National Bank Act, renaming itself the First National Bank of Pittsburgh. PNC’s headquarters building-completed in 2015 and billed at the time as one of most environmentally friendly office towers in the country-occupies the same Fifth Avenue and Wood Street location in downtown Pittsburgh as its Civil War-era predecessor.

PNC is a product of the industry’s consolidation over the past two decades, having made a number of significant acquisitions including Cleveland-based National City Corp. in 2008, which took PNC into several Midwestern states, and the U.S.-based retail banking operations of the Royal Bank of Canada, which expanded PNC’s franchise into the Southeast. At the end of last year, the bank had 2,529 branches in 19 states and the District of Columbia, with its footprint extending west to Missouri, north to New York and Michigan, and south through the Carolinas and Georgia to Florida. Its primary businesses include corporate lending and related fee-based services, a traditional strength of the company; retail branch banking; investment management, including a 22 percent stake in BlackRock, the world’s largest asset manager; and consumer products like mortgage, student loans, credit cards and auto financing.

Demchak, who was born in Rochester, New York, but grew up in Pittsburgh, has an undergraduate degree from Allegheny College in Western Pennsylvania, where he was elected to the Phi Beta Kappa honor society, and later received an MBA from the University of Michigan. He started his banking career at what was then J.P. Morgan & Co. in New York, which included a stint as the global head of Morgan’s structured finance and credit portfolio. Demchak stayed on after Morgan was acquired by Chase Manhattan Corp. in 2000, although he once told an interviewer that the post-merger company “wasn’t a terribly enjoyable place to work,” then jumped to PNC in 2003 to become its chief financial officer.

PNC is known for being very conservative when it comes to credit. Allen Tischler, a senior vice president and credit analyst at Moody’s Investors Service, says the bank’s conservative credit culture is most tangible in two areas: a disciplined approach to loan growth and a low level of concentration risk. “They have always advertised themselves as having a modest risk profile,” says Tischler. “You saw that during the last downturn when they didn’t report any quarterly losses.”

Given the bank’s culture and his own credit background, perhaps it wasn’t surprising when Demchak drew a line in the sand last year and decided that he would not further commoditize his corporate loan product by competing on price. But the decision did come at a cost to the company’s profitability. PNC’s reported earnings for 2016, at $3.98 billion, were off 3.6 percent from 2015. (Total revenue was down 1.4 percent in a year-over-year comparison.) The bank’s net interest margin remained virtually unchanged, at 2.73 percent, for the year.

Demchak believes that he made the right decision to pull back from the corporate lending market, where competition has resulted in lower spreads, weaker loan structures and longer terms. “We’re a conservative bank in terms of what we’ll do in credit and how we leverage the balance sheet as it relates to interest rates,” he says. “We purposefully underinvested in interest rate exposure so that the basic amount of money that we made on our deposits was less than what it otherwise could be.”

By Demchak’s calculation, the lost opportunity cost last year of not stretching for yield in PNC’s securities portfolio, but instead keeping about $30 billion on deposit at the Federal Reserve, was about 60 basis points. “If you choose to take that extra 60 basis points, you’re giving up the opportunity to do what we’re doing now in a higher rate environment and invest the cash at higher rates,” he says.

PNC should benefit from Demchak’s decision to stay on the sidelines last year if rates go up in 2017, as they now seem poised to do. Brian Klock, an analyst at Keefe Bruyette & Woods, says that PNC’s high cash balances represent “stored earnings power” that can be deployed into either higher yielding securities or loans. The bank’s balance sheet is asset sensitive, so it has plenty of ammunition on hand. Klock says that institutional investors appreciate PNC’s conservative nature, and while they want the bank to grow, they want it to do so profitably. “I think investors would tell you that, ‘Look, we own this thing because we want [PNC] to grow…but put on profitable growth because we’re paying a higher multiple for [the stock].’”

Still, Demchak freely admits that PNC has been “under earning for a bunch of years,” and the profitability of the bank needs to improve. He says that a return on average equity (ROAE) of 12 percent to 13 percent, depending where the bank is in the business cycle, is attainable. The bank’s ROAE last year was 8.85 percent, down from 9.5 percent in 2015.

But how to get there? PNC’s most immediate opportunity for an uplift in profitability lies in its corporate and institutional bank, which comprises its largest business. The operation earned a little over $2 billion after taxes in 2016, which was essentially flat compared to 2015, although total loans did increase slightly in a year-over-year comparison. Demchak says an important piece of his strategic plan is to increase PNC’s market share in the newer parts of its geographical franchise, particularly the Midwest and Southeast. “Those newer markets have been growing almost across every product at double the pace of our traditional markets and continue to do so,” he says. PNC also has a sophisticated suite of fee-based services that it sells to its corporate borrowers, and those are a significant source of revenue. As the bank expands its market share on the credit side, this opens up opportunities to cross-sell its fee-based products. “You have an incredible competitive advantage if you have good products, and we do,” he says.

A stronger U.S. economy would certainly help the growth of PNC’s corporate lending business, and during the presidential campaign Donald Trump said he wanted to cut the corporate tax rate and fund a large infrastructure spending program, both of which could help stimulate economic growth. Anything that stimulates corporate borrowing would help PNC, but the bank is likely to benefit more quickly from a rise in rates given that its balance sheet is asset sensitive and loaded with cash. “I think the impact from short-term interest rates will be more important to their earnings over the next five years than the pick up in the rate of loan growth,” says Tom Brown, CEO of the hedge fund Second Curve Capital and a longtime investor in banks and other financial services companies.

The business with the greatest opportunity to materially change PNC’s profitability over the next several years is the retail banking operation, which earned about half of what the corporate and institutional bank did in 2016. Part of the difference can be explained by the wide disparity in costs between the two units. The corporate bank had an efficiency ratio of just 39 percent compared to 71 percent for the retail bank. (To simplify, that means it cost 71 cents for every $1 in revenue to operate the retail bank. The bank’s overall efficiency ratio in 2016 was 62 percent, unchanged from 2015.) A big part of that difference is the high overhead of running a large branch network, and this is where Demchak’s push to place greater emphasis on digital distribution could really pay off.

The shift in consumer preferences toward digital has been just as dramatic at PNC as at most other banks. “Sixty percent of our [retail] clients would self-identify as primarily digital clients,” Demchak says. “Fifty-two percent of our check deposits are taken through imaging, either at an ATM or through a phone, and it’s growing every day. If you think about that you say, ‘Wow, 60 percent of my clients are no longer having face-to-face conversations with me.’ I have a dramatically different customer proposition that I have to offer in order to maintain my brand loyalty. That takes you down this path of ubiquitous, channel-agnostic service for clients, whether they’re coming through a call center, through mobile, through online or through the branch.”

PNC has also invested $1 billion in upgrading its core technology system, which entailed putting all of its retail apps in a private cloud, backed by a new data center. This will allow PNC to respond more quickly to changing market trends in retail product design and delivery, much of it driven by fast moving fintech companies. PNC is also debating internally whether to publish its application programming interfaces, or APIs, giving third-party developers access to its data, which they can use to create new apps for its customers to use.

With retail transaction volume shifting increasingly to digital channels, the bank has closed 421 branches since the end of 2011, and has been converting many of its remaining locations to a new “universal branch design” that eliminates the traditional teller line in favor of an open floor plan. The universal branches have image-enabled ATMs that can handle all basic transactions, and instead of tellers, they are mostly staffed with customer service representatives who can assist customers with mortgages, car loans and student loans. The bank has already converted 21 percent of its branches to this new platform and expects to convert 50 percent by 2020. The bank also has been rolling out smaller, 160-square-foot “pop-up” branches in certain markets that provide ATMs for all transactions and are staffed by a representative who can provide advice on PNC products.

Like all banks, PNC faces the challenge of managing across a growing demographic divide. Many older customers still prefer branches, while many millennials prefer digital. “It’s this balancing act of keeping your existing customer base happy as you build for the future of what the next generation of bank user will be,” Demchak says. “The branches can be further apart and more specialized than they are today, but I do think there will always be physical branches. I think they’ll be important for trust, client service and problem resolution.”

The third big change that Demchak wants to make in the retail operation is to place more emphasis on consumer lending. This isn’t so much a reaction to online marketplace lenders like Lending Club and SoFi as it is the recognition that putting more consumer loans on the books would improve PNC’s net interest margin since spreads are generally wider than in the corporate sector. The bank recently launched an unsecured consumer credit product that is underwritten using internal customer data as well as FICO scores, and it also has a preapproved car loan product called “Check Ready,” which its customers can use when they go to a dealership. Both products are available through the bank’s mobile channel. While he has not discussed this with Demchak, Brown says, “I would not be shocked if PNC, in the next couple of years, develops a new brand for a digital-only bank.

Demchak is pushing consumer lending because he knows that PNC needs more balance in its loan portfolio, which is heavily weighted toward corporate loans. “We’ll get grief occasionally about our efficiency ratio, which is a pre-provision, expenses-to-revenue metric,” he says. “We’re not over-spending. In fact, we’ve held expenses down or flat for four years. We’re under-earning.” And part of the solution, he adds, will be “getting more balance through time on our consumer [loan] book versus our C&I [loan] book.”

Something that won’t be a part of Demchak’s strategic plan going forward is the acquisition game, which historically PNC has played quite well. “I think with a traditional bank deal today, we’d be buying yesterday’s problems,” he says. “[You would be buying] old branches, and they’re typically in the wrong place.”

Acquisitions served their purpose when PNC wanted to scale its footprint beyond Western Pennsylvania, but now its natural evolution needs to emphasize better rather than bigger. Or different-more in line with where the world is heading.

Brown at Second Curve credits Demchak, along with Capital One Financial Corp. Chairman and CEO Richard Fairbank-another Darwinian banker-with understanding that “the business is changing, we’ve got to change how we do business and we can’t afford to be making acquisitions while we are changing both the front and the back end of our companies to become digitally centric.” Brown sees Demchak as a rising talent in the banking industry who could have an impact that expands well beyond his own company. “He is going to be for a very long time, if he wants it, an industry star as CEO.”

Join OUr Community

Bank Director’s annual Bank Services Membership Program combines Bank Director’s extensive online library of director training materials, conferences, our quarterly publication, and access to FinXTech Connect.

Become a Member

Our commitment to those leaders who believe a strong board makes a strong bank never wavers.