The Banker at the OCC

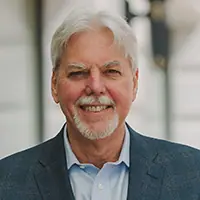

For that reason alone, the current comptroller-Joseph Otting-is something of an anomaly. Otting is a former banker who has never served in government, unlike his predecessor Thomas J. Curry, who had been a state bank regulator in Massachusetts and later served on the board of the Federal Deposit Insurance Corp. before his appointment in 2012, and Curry’s predecessor John C. Dugan, who worked in the Treasury Department and as a minority counsel in the U.S. Senate before he became comptroller in 2005. (Keith Noreika, a lawyer with Simpson Thacher & Bartlett and member of President Donald Trump’s transition team within the Treasury, served as acting comptroller between Curry and Otting.)

The 61-year-old Otting, who took office in November of last year, was an unusual choice for another reason as well. In July 2011, Otting, who was then president and chief executive officer at Pasadena, California-based OneWest Bank, FSB, signed a consent order with the Office of Thrift Supervision stemming from thousands of mortgage loan foreclosure violations that occurred in 2009 and 2010. The OTS later merged into the OCC as part of the Dodd-Frank Act of 2010. This means that Otting now heads the successor to the agency that dropped the legal hammer on his bank while he was CEO.

Otting’s appointment, which was approved by the Senate in a close 54-43 vote, was opposed by most Senate Democrats during the confirmation process, although Democratic Sens. Joe Manchin from West Virginia and Heidi Heitkamp from North Dakota did vote for him, and others either skipped the vote or abstained. He was also strongly opposed by a number of consumer advocacy groups, including the California Reinvestment Coalition. “Are bank regulators there to work for banks, or are they there to ensure banks are safe and sound and not risking the economy?” said the organization’s executive director, Paulina Gonzalez, in an interview with the Los Angeles Times. “Putting Joseph Otting in this position is risking the livelihood of everyday Americans.”

However controversial his appointment may have been, Otting’s experience as a banker could bring-at least from the industry’s point of view-a fresh perspective to the job of regulating banks. Although all of the recent comptrollers before Otting had private sector experience as bank attorneys, none of them knew what it was like to run a business in an intensely regulated environment. Today’s bank regulatory system is a complex mélange of complicated rules administered by multiple agencies at the state and federal level, often with overlapping jurisdictions, in a political environment that has been nothing short of punitive since the financial crisis 10 years ago. “It’s appropriate that we regulate banks,” says Jo Ann Barefoot, CEO of the consulting firm Barefoot Innovation Group and a former deputy comptroller at the OCC, “but it’s hard to be regulated.”

In two extended interviews with Bank Director magazine, Otting expresses support for the industry to which he has devoted his entire professional life. Asked directly if he would be more likely to go easy on the banks under the OCC’s supervision because of his background, Otting says the opposite is true. “I think you’d have the tendency to be tougher,” he says. “You understand what is right and wrong, and you make those [tough] decisions if you have a stiff spine. There’s a right way and a wrong way to do things.” But Otting does want to simplify some of the more burdensome rules that banks must adhere to, and that parallels efforts in the U.S. Senate to scale back some of the provisions of Dodd-Frank, which tightened regulation on the industry after the financial crisis.

Although the foreclosure controversy surrounding his tenure at OneWest created a credibility issue in the minds of his critics, Otting’s tenure as comptroller will ultimately be judged by how well he balances his desire to ease the industry’s regulatory burden with the safety and soundness of national banks, including some of the country’s largest institutions. “He’s a talented and well-meaning professional. He has the ability to do well, but like all comptrollers his tenure will be fundamentally judged by the health of the national banking system,” says Eugene Ludwig, CEO of Promontory Financial Group and himself a former comptroller. Ludwig, who was appointed by President Bill Clinton in 1993 and served a full five-year term, says he was brought to the OCC to in part help deregulate the banking industry, and he understands the challenge facing Otting if he wants to be both a regulator and a deregulator. “You’ve got to show exquisite balance, and I think he knows that,” says Ludwig, who met with Otting after he arrived at the OCC.

The role of the OCC is to supervise nationally chartered banks, including the likes of JPMorgan Chase & Co., Wells Fargo & Co. and Bank of America Corp. In fact, eight of the 10 largest U.S. banks are supervised by the OCC, all of which can be presumed to pose, to varying degrees, a systemic risk to the nation’s economy should they get into trouble.

Although there may be some degree of paternal pride involved, both Curry and Ludwig consider the OCC to be the preeminent bank regulator, surpassing even the exalted Federal Reserve in its grasp of what makes a bank tick-or fail. “It’s a highly professional organization,” says Curry, who is now co-lead of the banking and financial services group at the Boston law firm Nutter McClennen & Fish. “I think in terms of the level of training and sophistication, the OCC is probably the tops among the regulators. It’s certainly at the top of the heap when you look internationally as well. So there’s a lot of pride there.”

Ludwig says that the agency’s examiners are capable of functioning almost like super auditors. “They are highly knowledgeable about banking-that’s how OCC’ers are trained-and knowledgeable about other institutions’ practices,” he says. “They can really add value in improving your practices when they’re on their game, and many OCC’ers are just wonderful at it. And behind closed doors, senior Fed officials will admit that OCC’ers are very skilled at it. It’s the nature of the organization. It’s not an economist-driven organization; it’s an examiner-driven organization.”

The OCC did gain the reputation in the years following the financial crisis of being a tough regulator, although the times themselves were very challenging as the agency dealt with hundreds of banks that were undercapitalized and hemorrhaging loan losses from commercial real estate or home mortgages. “There was a feeling after the crisis that they were the toughest examiners, and our guys were complaining quite a bit that the OCC examinations tended to apply large bank rules to small banks, and there wasn’t enough tiering,” says Chris Cole, executive vice president and senior regulatory counsel for the Independent Community Bankers of America, which represents mostly small community banks. “They were the tougher examiner in 2012, 2013, and you saw a number of banks convert from national charters to state charters, and some of that was because of the feeling that the OCC was too strict. But now I think that has changed, and it’s thought of as a very good regulatory agency.”

But while the OCC is highly regarded, it is difficult to entirely separate the reputation of the agency from the person leading it. Asked how he would rank the OCC among the federal banking agencies, one veteran banking attorney who has advised several of the country’s largest banks and knows the agency well says, “It depends on who’s running it.”

The home foreclosure controversy at OneWest and Otting’s involvement as CEO was a major issue during his confirmation hearings in the Senate. “You permitted your bank to break the rules, while in the process making life harder for homeowners … across the country trying to stay in their homes,” said Democratic Sen. Sherrod Brown of Ohio, the ranking member of the Senate Banking Committee, during the hearing. “How do we trust that you won’t allow banks to skirt the rules and hurt their customers as their regulator?”

The accusations against OneWest were that its mortgage foreclosure practices violated federal law, including so-called robo-signing practices where the bank automatically signed foreclosure papers without reviewing them properly. OneWest was formed in 2009, when an investor group headed by current Treasury Secretary Steve Mnuchin, a former Goldman Sachs investment banker, acquired the California-based IndyMac Federal Bank from the FDIC. Otting joined the newly-named OneWest in October 2010 as president and CEO. IndyMac had been an aggressive underwriter of subprime mortgages, and the OneWest team inherited a large number of delinquent home loans that either had to be modified and returned to performing status or foreclosed upon.

Otting says that it’s a “false narrative” that OneWest was “the foreclosure king” that callously threw people out of their homes when they could no longer afford their mortgages. The IndyMac subprime mortgages that OneWest assumed when it acquired the bank had caused a “five-alarm fire,” and “we were the firefighters that showed up to try to fix a very bad situation,” Otting says. “We never foreclosed on a loan that we personally made in that bank,” he says, referring to OneWest. “We tried our hardest to keep people in their homes. We met every Friday as a management team and went over the most complicated cases trying to figure out how we could keep people in their homes.” Looking back on it now, Otting says, “We did whatever we could to help people transition from a situation they never should have been in, and it was unfortunate. I think we did an incredible job.”

Still, OneWest was one of 14 banks that in April 2011 signed a consent order with the OTS over their foreclosure practices. Otting, who had only been at the bank for six months at that point and signed the order as CEO, says he had no choice. “I did not sleep for many nights thinking about whether I was going to sign that consent order or not,” he says. “I had just joined the bank, and basically I was signing something that I never allowed any institution that I was involved with to be dragged into. At the end of the day, we did not have a choice [but] to sign that consent order. If I didn’t sign it, there would not have been a OneWest Bank.”

The consent order also required all 14 banks to go through an independent foreclosure review, and OneWest is on record as being the only bank to have successfully completed the process. A report issued by the OCC in April 2014 found that just 5.6 percent of IndyMac borrowers were due some type of financial remediation attributable to OneWest’s foreclosure practices, at a cost to the bank of $8.5 million.

If William Shakespeare is correct that “What’s past is prologue,” then Otting will bring his own personal perspective to his time in office. He grew up in Maquoketa, Iowa, a small community in the eastern part of the state. His father was an entrepreneur who owned a car dealership, among other businesses, and his mother was a school teacher. Both of his parents taught him the value of hard work and the importance of family. “Every day my mom and dad got up,” says Otting. “My mom fed the kids. We went off to school. My mom worked all day. My dad worked all day. And then we got together at night, and it was kind of a thing in our family that you had to be home for supper unless you had some sort of pass, and those passes didn’t come very often, unless there was something specifically around athletics or academics that took you away.” The lesson he learned growing up, Otting says now, was that “you were going to go into the mainstream of life similar to your parents … and be productive citizens.”

After Otting graduated from the University of Northern Iowa with a management degree, he was offered two jobs. One was with the Coca Cola Co. in Atlanta; the other was with Bank of America in California. He chose the latter, in part because of his father’s advice that banking would give him a broader exposure to the business world. Otting would eventually work in senior positions at Union Bank and U.S. Bancorp before joining OneWest.

A career spent in banking has given Otting a deep regard for the positive role that banks play in the economy, a view that is at odds with a competing narrative that banks pose an existential threat to the economy and must be tightly controlled. “My personal viewpoint is that they are really at the core of most communities,” he says. “What bankers get the opportunity to do is help people fulfill their dreams.”

Otting doesn’t dispute that the practices of some banks contributed to the crisis. “We as a nation went through a very difficult period that touched a lot of people in a very negative manner,” he says. “There were attributes of the banking industry that contributed to that.” But he still believes in the importance of banks and the inherent goodness of most bankers. “I think banks play an invaluable and significant role in any community across America,” he says.

Although his recent predecessors who were banking lawyers before they became the comptroller understood the industry from a legal and regulatory context, Otting brings a business and operational perspective that is unique. “I understand credit risk. I could underwrite any loan that comes through, and look at it quickly and tell you whether it’s a good loan or not a good loan,” Otting says. “I understand BSA [the Bank Secrecy Act]. I understand interest rate risk management. I understand CRA [the Community Reinvestment Act], because I’ve managed CRA programs.” Otting believes that this professional background will allow him to “immediately focus on the things that I think [will] make the agency better, and policies that perhaps will not increase risk, but allow the industry to operate in a more effective manner.”

Ludwig credits Otting with bringing skills and experiences that will be extremely valuable in his new position. More importantly, perhaps, Ludwig also vouches for his good intentions, despite the chorus of criticism that Otting has received from Senate Democrats and consumer advocates. “I’m pretty confident, knowing him and having spent time with him, that he is thoroughly well meaning,” Ludwig says. “He respects the office and … respects the OCC’s excellence in examination and supervision. That’s a big plus, because many of us who came to the office had policy experience as lawyers and some experience with the examination and supervision staffs, but we weren’t supervised typically. He was.”

The winds of regulatory change are blowing out of Washington, D.C., and the appointment of a banker to head up the OCC is just one example of that. A new chair, Jerome Powell, and new vice chair for supervision, Randal Quarles, have been installed at the Federal Reserve. Like Otting, both have backgrounds in private sector finance. Jelena McWilliams, the chief legal officer at Fifth Third Bancorp, has been nominated by President Trump to head up the FDIC and awaits confirmation by the Senate, and a new permanent director of the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau will be appointed to replace interim Director Mick Mulvaney, who has already unwound several of the agency’s policies. “Our guys are very optimistic about the changing of the guard, and they see this as an excellent opportunity to change some rules [and] reduce the burden of regulation,” says the ICBA’s Cole.

As this story went to press in late March, the Senate had passed a bill introduced by Republican Sen. Mike Crapo of Idaho, chairman of the Senate Banking Committee, which would loosen many of the Dodd-Frank restrictions, including an increase in the designation threshold for systemically important financial institutions, which are subject to stricter supervision by the Fed, from $50 billion in assets to $250 billion.

Cole is hopeful that the House of Representatives will pass the Senate bill pretty much as is, although Jeb Hensarling, a Republican congressman from Texas who chairs the House Financial Services Committee, has already said publicly that the Senate measure does not go far enough. The House passed its own, more aggressive bank deregulation bill last year, sponsored by Hensarling, who says he wants a number of features from that bill incorporated in any legislation that eventually reaches Trump’s desk. However, several senators in both parties have pushed back against Hensarling’s demands, so the fate of bank deregulation in 2018 remains unclear.

Bart Naylor, a financial policy advocate with Public Citizen who voiced strong opposition to Otting’s appointment, opposed both the Hensarling and Crapo deregulation bills but says he’s more concerned that “the real damage to banks’ prudential supervision is going to be done by the regulators themselves.” And this speaks directly to the authority that Otting and his peers have to change the game of bank regulation. Otting has “considerable latitude” in his authority as comptroller, according to Ludwig. “What really impacts banking organizations the most is the application of the rules and regulations,” Ludwig says. “The regulatory agencies had enough authority under existing legislation [after the financial crisis] to do immensely powerful things in terms of being more demanding of banks. Dodd-Frank was valuable in setting a direction and setting priorities, but they didn’t need it.”

When asked if he thinks of himself as a deregulator, Otting says, no, he does not. But he does want to look for ways to simplify the rules for the Bank Secrecy Act, the Community Reinvestment Act, and capital requirements for small banks. The purpose is not to weaken these rules in ways that would pose a threat to safety and soundness, Otting says, but to make the rules easier and less costly to comply with. “I am a supporter of Dodd-Frank, but I do think there are provisions where we can round the edges to allow the industry to operate in a safe and sound manner, [and] to redirect an enormous amount of resources that are internally focused to their customers and the markets in which they operate,” he says.

In the realm of BSA, for example, Otting points out that just a very small percentage of transactions warrant the filing of a suspicious activity report-and law enforcement agencies look at an even smaller percentage of reports that are filed-but there is a low tolerance for error when it comes to compliance. One possible solution that Otting suggests would be the creation of an industry-wide database of all bank transactions that would enable law enforcement agencies to do their own search for criminal activity.

Otting also describes the current CRA law as “highly complex, difficult to regulate [and] difficult to implement.” He believes that a new measurement criterion that applies universally across the industry, along with an expansion of what qualifies as a CRA investment and changes in the CRA examination process that would provide more immediate feedback on a bank’s compliance performance, would result in more money flowing to low- and moderate-income neighborhoods. A third regulatory issue that Otting says should be addressed is the simplification of the capital requirements for small banks, not to reduce their capitalization but to make it simpler for them to comply.

Whether Otting is a deregulator or just wants to “round the edges” of complex laws like Dodd-Frank is really a question of semantics. The reality is that he’s bringing new ideas about regulation to the OCC at a time when the country’s political structure-including Congress and what eventually will be a new team of bank regulators-seems to be embracing the idea of deregulation. But Otting’s predecessor as comptroller, Thomas Curry, believes that the financial crisis-which begat Dodd-Frank-also resulted in a “broad consensus” on the importance of having a well-capitalized and conservatively managed industry. “That doesn’t mean there’s not going to be fine tuning or adjustment along the edges,” Curry says. “As long as we don’t have a wide swing from where we are, I think we’ll continue to have a safe and sound banking industry. But more radical changes can result in more radical consequences.”

Join OUr Community

Bank Director’s annual Bank Services Membership Program combines Bank Director’s extensive online library of director training materials, conferences, our quarterly publication, and access to FinXTech Connect.

Become a Member

Our commitment to those leaders who believe a strong board makes a strong bank never wavers.